VXLAN // MP-BGP EVPN

If you aren’t familiar with VXLAN, check out my initial post on VXLAN to get an idea of what it is.

We’re going to expand on that topic in terms of how it works. Before we talk about VXLAN with MP-BGP EVPN, it’s important to understand how traditional VXLAN works, and what some of the shortcomings are.

Flood-and-Learn VXLAN Control Plane (i.e. no control plane)

By default, as per RFC 7348, VXLAN works using a multicast-based flood-and-learn method. This works by sending everything out the data plane and not really having anything for a control plane. Any BUM traffic (Heh I know what you’re thinking, but it stands for Broadcast, Unknown Unicast, Multicast – also one of the best three-letter-acronym’s in IT), hits the underlay network, maps to a multicast network, and sends everything out that way.

For example: In a non-VXLAN environment, if a host was to send a packet to another host without knowing its MAC address on the same segment, the host would send an ARP via broadcasting it to the entire L2 segment. With VXLAN, the ARP is sent to the multicast group that the VXLAN process uses. Essentially, you map the VNI to a multicast group and flood that multicast group with the ARP (or any other BUM) traffic.

If you have multicast set up on your network and love managing it, then sure, go for it. Otherwise, it’s a pain to manage and stay the ** away from it. As I’ll explain below, there’s a few more advantages as well with going the MP-BGP way.

Also – by not having a control plane, there’s no real way to “discover” the VXLAN fabric. This means that any host can join in on the VXLAN system and start sending traffic; whether legitimate or malicious. Obviously this presents a security issue, as well as a management nightmare.

MP-BGP EVPN

Try saying that 10 times in a row. The excessively long acronym stands for Multi-Protocol Border Gateway Protocol with the Ethernet Virtual Private Network address family. Damn that’s a complicated name.

Essentially what we’re doing is using the EVPN address family within BGP (well…MP-BGP, but let’s just assume BGP in this context = MP-BGP…) to propagate the same kind of BUM (makes me giggle every time) traffic we talked about above. The idea is we create a control plane that we use to reduce the traffic on the fabric (and not use multicast), which consequentially also helps make the solution quite a bit more scalable. As you’ll see a little further in this post, doing this helps drastically reduce flooding in the fabric. Some of the more interesting side-effects of doing this; you have the ability (should you choose) to start supressing ARP in the fabric, and also do anycast gateways; which essentially means that every node in your fabric can have a local gateway.

Using the Network Layer Reachibility Information (NLRI) that’s collected by EVPN, VXLAN builds an understanding of who’s on each VNI, and only sends packets to its intended recipients. That is – it sends directed unicast to nodes on the network that it learnt via conversational learning (a method where MAC addresses are learnt by observing traffic from each connected host). If the BGP EVPN process doesn’t know about a host, the packet intended for that host gets dropped, and doesn’t flood the fabric.

From Cisco’s perspective, they say that going MP-BGP for the control plane provides the following benefits (direct quote from Cisco):

- The MP-BGP EVPN protocol is based on industry standards, allowing multivendor interoperability.

- It enables control-plane learning of end-host Layer-2 and Layer-3 reachability information, enabling organizations to build more robust and scalable VXLAN overlay networks.

- It uses the decade-old MP-BGP VPN technology to support scalable multitenant VXLAN overlay networks.

- The EVPN address family carries both Layer-2 and Layer-3 reachability information, thus providing integrated bridging and routing in VXLAN overlay networks.

- It minimizes network flooding through protocol-based host MAC/IP route distribution and Address Resolution Protocol (ARP) suppression on the local VTEPs.

- It provides optimal forwarding for east-west and north-south traffic and supports workload mobility with the distributed anycast function.

- It provides VTEP peer discovery and authentication, mitigating the risk of rogue VTEPs in the VXLAN overlay network.

- It provides mechanisms for building active-active multihoming at Layer-2.

Alright – now how does it actually work?

It can be a little complicated, but the core of it is actually really simple:

- Local Learning: the VTEP learns about the locally connected hosts’ MAC address and IP information (i.e. NLRI) by listening to the Source MAC addresses, ARP/GARP/RARP.

- Distribute that NLRI information by propagating the locally learnt information into the EVPN process. Typically, the information that’s sent across is the route distinguisher, MAC Address length, MAC address, IP address length, IP address, as well as the L2 and L3 VNI information.

- Use either Synchronous or Asynchronous Integrated Routing and Bridging (IRB)

Asynchronous IRB

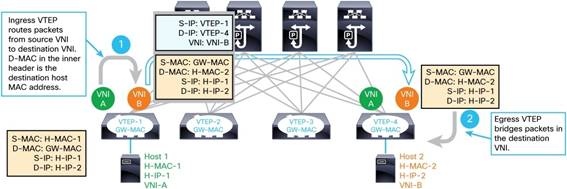

First - Every VTEP is configured on every switch so that the leafs can learn the ARP entries and MAC addresses. After this, the ingress VNI routes the packet to the egress VTEP on the local ingress switch, then sends it across the fabric where the only operation at the egress switch is local bridging.

Cisco has a somewhat convoluted image describing this:

(Figure 3 on Cisco’s Nexus 9000 Page)

Synchronous IRB

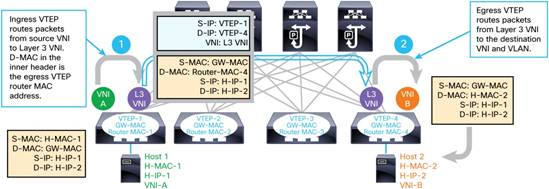

The synchronous IRB method is does the same thing as it’s asynchronous counterpart, with exception for one major part – instead of routing to the egress VNI, we route to an intermediate transit VNI (the L3 VNI) which exists on every leaf. This way – instead of having to create every VNI on every switch, we only have any relevant VNI’s, and the unique L3 transit VNI to move the packets along. Another advantage of doing it this way, is that a switch doesn’t need to learn about MAC addresses that aren’t relevant to it (i.e. if it doesn’t have local hosts on a specific VNI, it doesn’t need to learn remote MAC addresses on that VNI).

(Figure 5 on Cisco’s Nexus 9000 Page)

Inter-VXLAN Routing

The concept of Inter-VXLAN routing is similar to Inter-VLAN routing; in the sense that you are trying to move traffic between two different hosts on two different segments. In Inter-VXLAN routing, we use the concept of Layer-2 and Layer-3 VNI’s. If the frame belongs to the same VTEP, The L2 VNI is used to move traffic within the same VNI. However, if the local VTEP doesn’t have the MAC address in it’s database, it does a look up to find where the host is, encapsulates the packet in the L3 VNI header, and sends it across the fabric to the remote VTEP; where it gets decapsulated when it reaches the right switch. At this point, does the L2 VNI lookup and finds the right MAC address in the underlay, and sends it towards that switch and port.

Fabric Discovery

Unlike the flood-and-learn VXLAN method, having a proper control plane means that we can manage how nodes are joined to the fabric. Only once there’s BGP adjacency between nodes or Route Reflectors (RR) can the node start sending/receiving VXLAN traffic. Without this, the node doesn’t get added to a VTEP peer whitelist, and the traffic doesn’t propagate across the fabric to the unregistered node. Another interesting note about the discovery process is that since we rely on the iBGP session to be established, we can secure the session by adding a password within the BGP neighbour configuration to help disable any unauthorized nodes from joining the fabric.

++Thanks to Steven Harnarain for helping proofread my terrible grammar =)